Friends and Writers,

I am happy to share with you that RHINO Poetry has posted online a recording of my poem, “Small Animals,” which the editors so kindly published in their 2012 anthology. Have a listen here.

I became interested in making audio versions of my poems after I was a finalist in The Missouri Review’s 2011 Audio Competition. You can hear that piece, a poem for two voices called “Know/Don’t Know,” here.

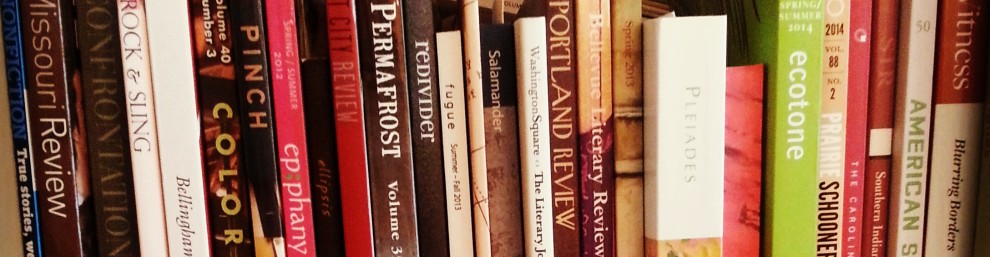

In the last year or so, I have made a number of recordings of my work, and some of these are here on my website (click “Home”). Some of these I cannot release yet, as the recorded poems are forthcoming in print forms in magazines like Bellingham Review and Quiddity–and Quiddity has its own public radio program, in which selected pieces from the journal are presented in audio format.

In my community workshops, I have referenced audio literature at StoryCorps, Soundzine, Drunken Boat, and From the Fishouse among other outlets of quality audio literature.

I find that much of the available audio content is in the genre of poetry. This got me to thinking…why? Why should we record our poems? For that matter, why should we record anything we write? I would encourage you to consider making some recordings of your work, so you can discover your own answers to these questions. Here are some of mine.

I find I have responses on two fronts. First, what does an audio format provide the audience that print text (whether on paper or on a screen) does not? As we know, reading and listening–though deeply connected–are not identical cognitive processes. Some of your audience may be better able to enjoy your work in an auditory format, or in an environment where both audio and visual formats are presented at once. Audio literature is very often delivered today via the internet, and much of the content is free, making you work accessible to anyone with a connection.

In addition to accessibility, audio recordings also provide readers anywhere with an intimate connection to your work through experiencing it presented and interpreted in your one-of-a-kind-in-the-whole-wide-world physical voice–and it is my belief that the physical voice of our body connects deeply with the writing voice(s) we create. Every time I facilitate one of my workshops, in which we generate and verbally share new work (using the Amherst Writers and Artists [AWA] Method), I learn anew the gift and the magic of hearing a piece of writing in its creator’s voice. Nuances of pacing, rhythm and image surface and coalesce in ways that may never be able to be captured on the page–just as written music, for instance, does not contain a notation for every single physical gesture the musician must undertake in order to bring the piece to life. I am talking not only about accents here, or dialect, or age or any of those factors that influence an individual’s lexicon, pronunciation, articulation, etc.–these are certainly part of the body’s voice. But I am talking also about timbre, pitch and texture, breathing patterns and volume: all the ways the voice is a thing of the physical body, an instrument of the body’s own music. What a gift to the world, to have a record of your voice, singing its poems and memories and stories!

The second part of my response is to consider what the process of audio recording offers to the writer. Here I can speak only for myself, and my experience is that every time I record a poem, I am in a very particular way rewriting it. What I mean is, I come to understand that two words (for instance), though separate on the page, may be connected to form one word when I perform the piece aloud–and this means something: my imagination has been working quietly, here, and has left this tiny gem for me to find in my own bodily time. This is because the poem is a different poem if two words become one word.

For instance, recently, I made a recording of a poem that contained the phrase “mud swallows swirl / a chattering above.” “Mud swallows” refers to several species in the swallow family of birds. When I perform my poetry, my habit is to articulate very clearly and very strictly interpret stressed versus unstressed syllables. The friend who was helping me to record said, “What do you mean, ‘Mud swallows swirl?’ What is the ‘swirl’ and how does mud swallow it?” While I chose to change my articulation (from MUD SWAllows SWIRL to MUDswallows SWIRL), my friend brought to my attention a layer of understanding beneath the one I was intentionally crafting–indeed, this is a poem about our dead and about our dying, and also about the wild un-repeatable swirl that living is.

In addition to offering a fresh experience of the “sense” of a poem, I also find that recording my work helps me to really get to know it as a physical thing. Because I record multiple takes of almost every poem, I find by the end of the recording session that I settle into a visceral understanding of the piece as a fabric of sound. I can read it then, truly, as music that I have practiced and practiced, and my body knows where to breathe, where to pause and where to move forward gently. It knows when to speed up and to slow down, where to linger on repetitions of pitch or rhythmic figures, and where to let my breath carry the piece quietly into the silence from which it came and will come, someday, again.